5 Minutes w/ The Sociologist

/There’s something indescribable about in-the-moment irony. There’s an ingredient to this experience which accesses parts of the brain that other more mundane experiences simply can’t reach. My black experience in America is filled with such irony, and perhaps that explains, why more than any other topic, the black experience is what I enjoy babbling about most. In fact If my black experience were an outfit, and days were conversations, I’d be wearing the same outfit about 5 days a week— the other two days I’d be naked (but that’s another story for another day).

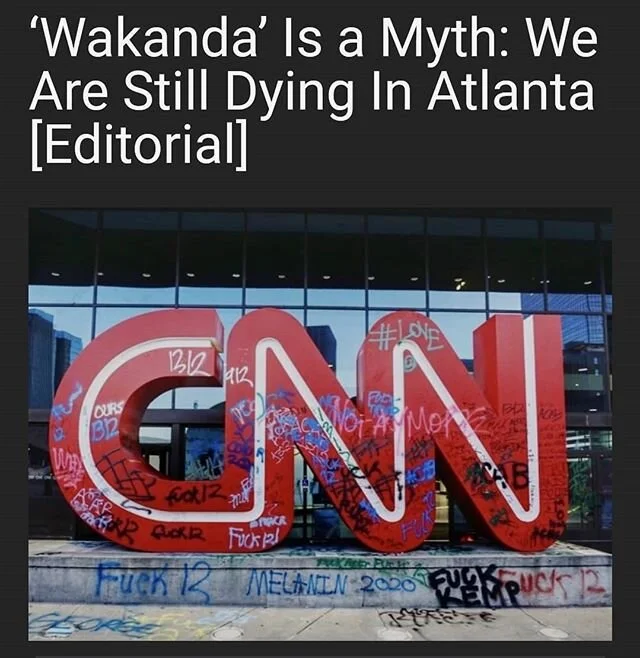

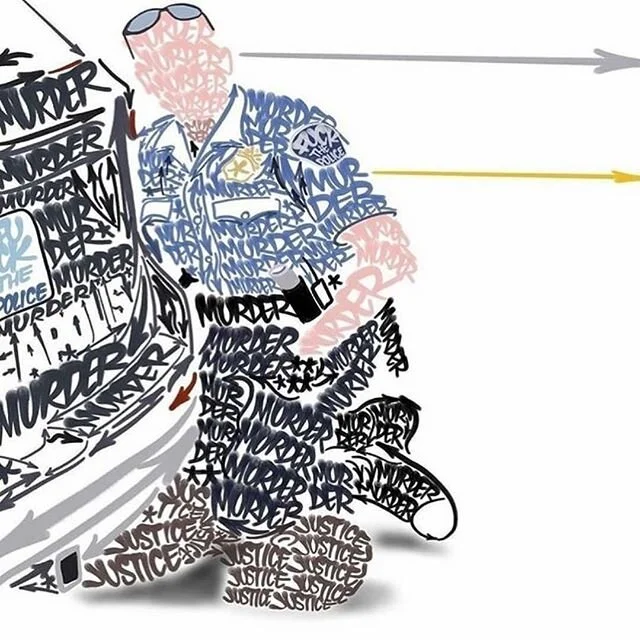

So there I was, slow-bopping my way through the historic Shaw neighborhood, once home to the largest urban population of black people in the District of Columbia. “Little Ethiopia” and several other black landmarks call Shaw home, while U Street, LeDroit Park, Howard University, and Bloomingdale all call Shaw their neighbor. This seemingly perfect placement has made Shaw the go-to neighborhood for many new residents. So in recent years, with demand to live in Shaw being so high, Shaw has all but lost the black population it once boasted, and many natives would argue it’s soul as well.

On this day I’m meeting up with a wonderful sociologist to talk about, of all things… Black people, love, and relationships. Now steps away from our meeting place I’m overwhelmed by the before-mentioned spirit of irony. Prepping myself to have a conversation about how to keep black people together through love, in a neighborhood that has all but pushed us out.

***

AW: Why love? Why focus on love as topic, as a discipline? Why?

JB: So I think looking at love is one of the most revolutionary things we can do for black folks… And I care about black people. I literally will only study black folks. And so I think that we often think about the work that has to be done with our people, and we think about the problems, we think about the challenges, the social ills, and all of that someone should do. I’m not going to do it, but someone should do—and someone is always doing it. There’s never a time where we’re not looking at the problems. But the thing is if we know we have these problems, how do we survive within them? The amount of *ish that we have to encounter, and go through, and struggle, and manage. Who could possibly need love more? For whom could it be more important than us? And so I see love as this power with the greatest healing potential. If we’re encountering all these things and dealing with all this stuff, love is absolutely essential to how we’ve made it, and if we’re going to grow.

AW: That’s a very big undertaking and it sounds like it could be emotionally draining, in what ways do you love yourself given the type of effort and energy you have to put forth to deal with the lack of love that may be present in your work?

JB: I think that’s the other-side of why I do what I do. I’m a sociologist by training. Sociologist study problems, and problems make you depressed. I don’t study problems. I study things that work, because I’m interested in how they work. So one of the things that I think is a challenge with a lot of social sciences, not just sociology, but as a whole is that we start with the problems. What’s the problem and how do we fix it? We start with the problems with the assumption that we actually know how it works, when it works well. So I started out way back as a chemist, and in chemistry what you know is you don’t start changing the reaction until you actually know how the reaction works in its most normal sense and I don’t think we actually know how things work when it comes to relationships because we always study the problems.

So before we start studying the problems and giving solutions and telling folks how they should change, all the “relationship experts”, all the counselors and other folks. How are we gonna tell people how to make things work, if we/they don’t actually know how they work? So for me the major influence was figuring out, how does it work? Because I don’t assume that we know how it works. So I actually don’t have to study the things that are problematic, I study relationships that work, that people have stayed in, that people have found ways to keep together and sustain. So in a lot of senses my work is the most cheerful sociology that you get. Because I get to begin to understand the process before I even begin to look at a problem.

AW: So what works? When you were talking I couldn’t help but to think about all the problems we hear about, and what’s not working. We’re giving the Intellectucool community a free session right here, what works? What is working for black people and love?

JB: (Exclamatory) With all the *ish that we go through and the fact that we stay together, attempt to get together! We talk about all the statistics and say why aren’t people staying together more— and I’m like are you kidding me?! With all the things thrown at our community all the time, and the fact that we even stay together at all! Because other folks (communities) have many more resources, time, etc. So the biggest things working for black folks staying together is black folks. We actually make stuff work. The unfortunate thing is that when it comes to black relationships we don’t talk about the couples and things that make stuff work enough. Instead we choose to focus on what’s problematic. The inventive spirit of black folks make things work. We make things work under insane pressure— so we work.

AW: (Slowy nods head and ends interview).

Jovonne J. Bickerstaff, a scholar of gender, race and emotion work, is a Postdoctoral Associate in the Mellon-funded African American History, Culture & Digital Humanities Initiative at University of Maryland, College Park. Her dissertation, “Together, Close, Resilient: Essays on Emotion Work Among Black Couples,” probed the emotion strategies partners co-construct to foster emotional intimacy, navigate differences and cultivate a shared identity - offering a rare window into black intimate lives. Centering and theorizing from the experience of black couples in enduring relationships (10-40 years), Bickerstaff's first book project brings an intersectional approach to Hochschild’s emotion management framework. It provides a more nuanced portrait of how gender matters and avoiding the gender essentialism in much of the research that takes the white, middle class as normative American couples. Her current work takes a more theoretical slant - proposing novel frames for conceptualizing black relationships beyond claims of crisis or caricatures of "black love," that attend instead to wellness, vulnerability and everyday expressions of care. Bickerstaff holds a BS in Creative Writing & BS in Urban Studies from MIT, an MPhil in Social Psychology from the Univ. of Cambridge and a MA & PhD in Sociology from Harvard where she was a Ford & NSF Fellow.